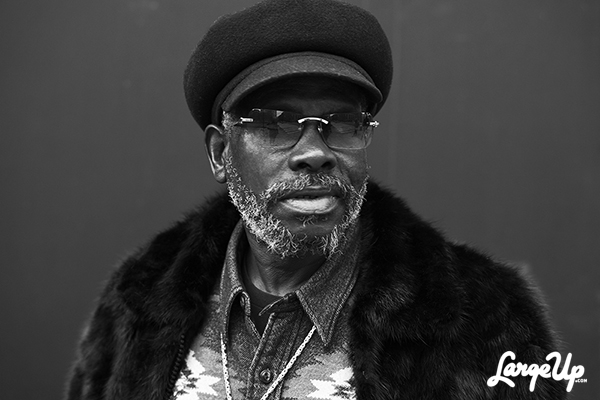

Words by Jesse Serwer, Interview by DJ Gravy, Photos by Aviva Klein—

Johnny Osbourne is, in many ways, the definitive dancehall vocalist. Not only has he most likely recorded more dubplates (that’s exclusive versions of popular songs tailored for play by a specific sound system, for you all you new-jacks) than any one else, his essential ’80s recordings like “Budy Bye,” “No Ice Cream Sound” and “Little Sound Boy” are some of the purest reflections of the real dancehall sound-system experience ever released commercially.

Interestingly enough, Osbourne began his career a decade before his peers from dancehall’s dawn in the late ’70s. But the very same day he finished his debut album, 1969’s Come Back Darling, for Winston Riley’s Techniques Records, he found himself emigrating to Canada, beginning the first of several hiatuses that would mark his uniquely paced career. Now, at age 65, Johnny finds himself with yet another fresh start before him. Major Lazer’s co-opting of his “Mr. Marshall” as the heart of their arena-rocking, dancehall-meets-dubstep anthem “Jah No Partial” comes just as the singer finds himself able to travel internationally for the first time in decades. Fresh off his very first European festival appearances and a long-awaited return to Jamaica, Johnny will make his first Florida performance in who-knows-when tomorrow night (3/21/2013) at LargeUp’s Winter Music Massive at Blackbird Ordinary in Miami. DJ Gravy recently sat down with the Dancehall Godfather in NYC, as photographer Aviva Klein snapped some intimate portraits. Let me hear you say whoa-oh!!

LargeUp: You’ve been current in more eras of Jamaican music than almost any other artist, from the ’60s until now. How were you able to stay current through all of those eras?

Johnny Osbourne: Well, I don’t [stay] stuck inna no zone. I have yesterday, today and tomorrow. I’m from the old school but mi always tell a man, I’m not stopped there and I don’t live there. I reinvent myself always. I’m full of ideas. My mind too young for mi body.

LU: You recorded your first album Come Back Darling in 1969. Is it true you left for Canada the same day?

JO: The same day we finished the album. In the early morning I took the photograph on the step of the first Air Jamaica plane that them bring, and in the afternoon I flew out to Canada. I never come back to Jamaica until 10 years after.

LU: What was the reason for going to Canada?

JO: My mom immigrated to Canada from about ‘64, ‘65. I have one brother and one sister and she was trying to get the three of us together. She filed for us from a long time but I wasn’t really [wanting] to leave Jamaica because I didn’t know that outside of Jamaica could be nicer than Jamaica. I thought Jamaica was so nice. I had to take myself off the filing paper and let my brother and sister go. Then my mother come to Jamaica in 1969 and said if I don’t come this time, she’s finished with me. And then Jamaica was getting really politically violent in that time. I figured my mother don’t want to stay in Canada and worry about me. I didn’t want to make my mother cry so I have to just go with my mother.

LU: What was Canada like for a Jamaican in the ‘70s?

JO: Well, for one thing, Canada is one of the coldest places for a while. After going [to] some other places, I realized how cold Canada is. For just leav[ing] Jamaica the first time at 22 years old, [it was] a culture shock. And then I loved the music, and reggae wasn’t catching on in Canada. North American never take reggae so hard like that. But still, the same way, they had a club called Club Jamaica—and on a Sunday evening they’d have an open mic ting. A few clubs did. I kept at it and loved it. But away from that, it was a struggle fi a while.

LU: There wasn’t a lot of opportunities to do reggae in Canada at that time…

JO: That time. But I never give it up, because that was a part of me. Mi love music. From I was young, I always wanted to be a Nat King Cole or a Johnny Mathis or a Sam Cooke or a Billy Eckstine or a Johnny Ace. That was some people I used to listen to and say yes, I have to be like them.

LU: You did soul music as well up there?

JO: To really eat some food at that time, [I] put some bands together. The work was club work. You get some reggae music but them want Top 40 from America and so forth. I had to do some Top 40 material.

LU: What was Ishan People all about?

JO: I moved around with a lot of different people but Ishan People was one of the more solid bands. I started to get more serious with di ting with Ishan People. David Clayton Thomas from Blood, Sweat & Tears heard Ishan People and produced an album before I joined. I joined the group, [and] David Thomas did a second album. Ishan People was doing some reggae, Bob Marley and a couple popular tunes but we were still writing and doing original songs. David Clayton Thomas produced it for JRT, a big company in Canada. It wasn’t Johnny Osbourne and Ishan People, it was just Ishan People, a whole band.

Read on for Part 2 as Johnny discusses his return to Jamaica after 10 years in Canada, and the birth of dancehall and the dubplate