ALRIC: Jamaicans, we always listened to a wide range of genres, but we listen wide, not deep. The only thing you could go deep into is reggae and dancehall. Everything else is whatever was popular in the day. That’s where I’m coming from. Boyd joined me and brought a deeper edge to the music at the time. At the time, hip-hop would be looked upon as just another part of the dance music set, or what we in Jamaica used to call the “disco” set. You would start playing hip-hop and gradually come up in the tempo—just one round, no separation. When Boyd came with that New York style, that was the first time the genres were played separate. We ended up developing a style where every genre is played in its true format. Not the bastardized format. How hip-hop is played in New York, that’s how we played it. How dancehall and reggae is played here, that’s how we played it. How dance music is played in New York and Europe, that’s how we played it.

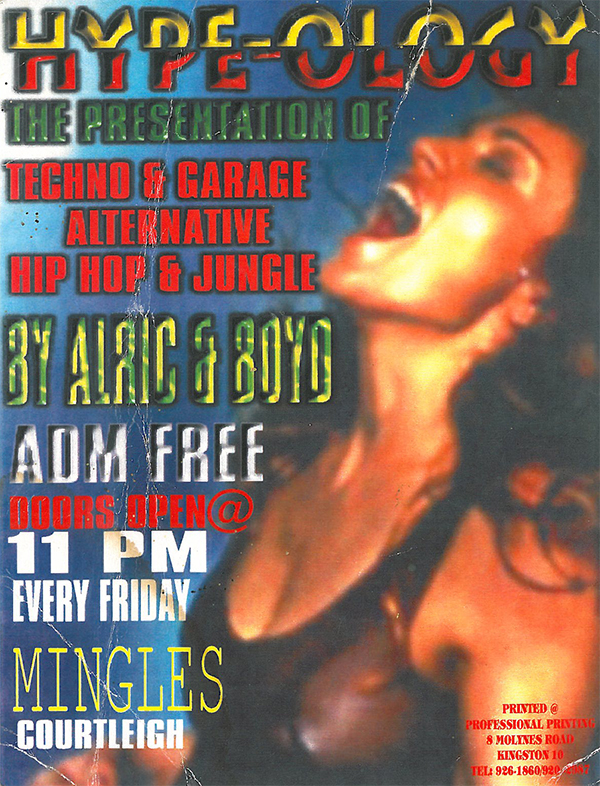

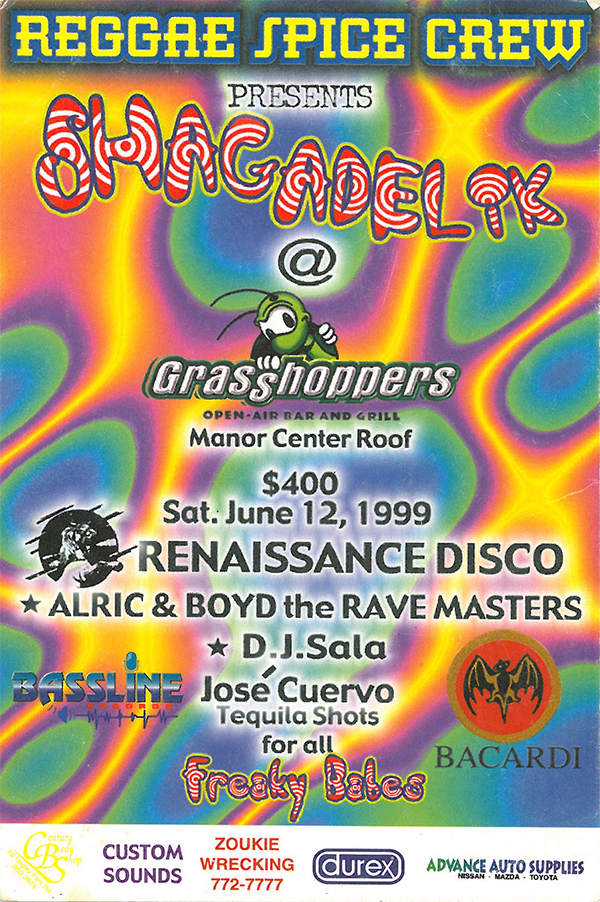

We started to carve a niche in the Jamaican pop culture that was ours, and created a unique space where everybody now was like, “what are these guys doing?” People who were exposed to it having traveled, they’d get what we were doing and say wicked, keep it going. A lot of people couldn’t understand what we were doing and we got boxed in a little.

BOYD: We joined Fame FM in 1995, and brought that approach to radio because that same bastardization of the genres used to happen on radio as well. In 1994, we had a chance of playing with DJ Squeeze on a show called Twin Towers. We used to play a lot of dance music on that show, and maybe 45 minutes of hip-hop. No dancehall. Wu Tang and Beatnuts, Pete Rock and CL Smooth—people were like how is that possible in Jamaica? And we used to take it to the dance side.

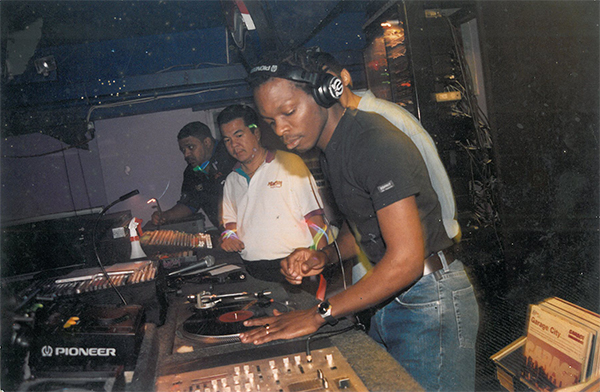

In the club now, we used to do a live remixing section where I would run the tracks I wanted to play under the commercial tracks that were popular in every club at the time—your Robyn S., [Cece Peniston’s] “Finally,” Crystal Waters— and create a whole different vibe, and show there’s other forms of club music that has a deeper vibe to it. Most of the tracks I wanted to play didn’t have vocals so I’d run it under and make the original track I was playing—that everybody knows—sound totally different. In Godfather’s, I’d play “Plastic Dreams” by Jaydee, a very dark techno song, and the dancers would go crazy. At that time they had dancers too, like how you had Bogle and everybody same way. Before Bogle was a dancehall dancer, he was a disco bwoy. Everybody don’t know that. He used to perform [as a dancer] on Ring Ding and TV entertainment shows back in the ‘70s, dancing to disco dance, not dancehall. He comes from the disco age, with the big shiny disco ball.

We found a way of breaking down the barriers between commercial and underground music. We’d throw in harder techno songs. And we realized there were people who liked that style of music. So when we brought it to radio in ’95, we expanded on it to get those people liking and digging for it more. Those were the days of turntables and vinyl. Label heads in the States think that the Caribbean is not a market that buys records. [Because] we would go to a store in New York or Miami and buy up a trailer load of records and ship them down. We had to import records from England, Germany, France. Literally all of our money went into buying records. You’re probably buying one record, one song, for maybe 8 to 15 pounds. But yet when you play the record, you are the only one in this hemisphere that has it. That really set us apart at the time. We made sure we mastered all the genres. If you want soca all night, we can give it to you, if you want hip-hop all night, we can give it to you. if you want dancehall all night, we can give it to you. And of course we can mix them up.

Click here for Part 3 of Alric and Boyd’s oral history of dance/EDM/rave culture in Jamaica