Photos by Colin Williams

It’s bacchanal season in the Caribbean once again, with Vincy Mas (St. Vincent), Spice Mas (Grenada), Crop Over (Barbados), Nevis Culturama and Antigua and St. Lucia Carnival (not to mention Caribana up in Toronto) all set to unfold over the next two months. Meanwhile, it’s been four months since the gold standard of all island celebrations took place in Port of Spain, but we’re still taking stock of this year’s Trinidad Carnival.

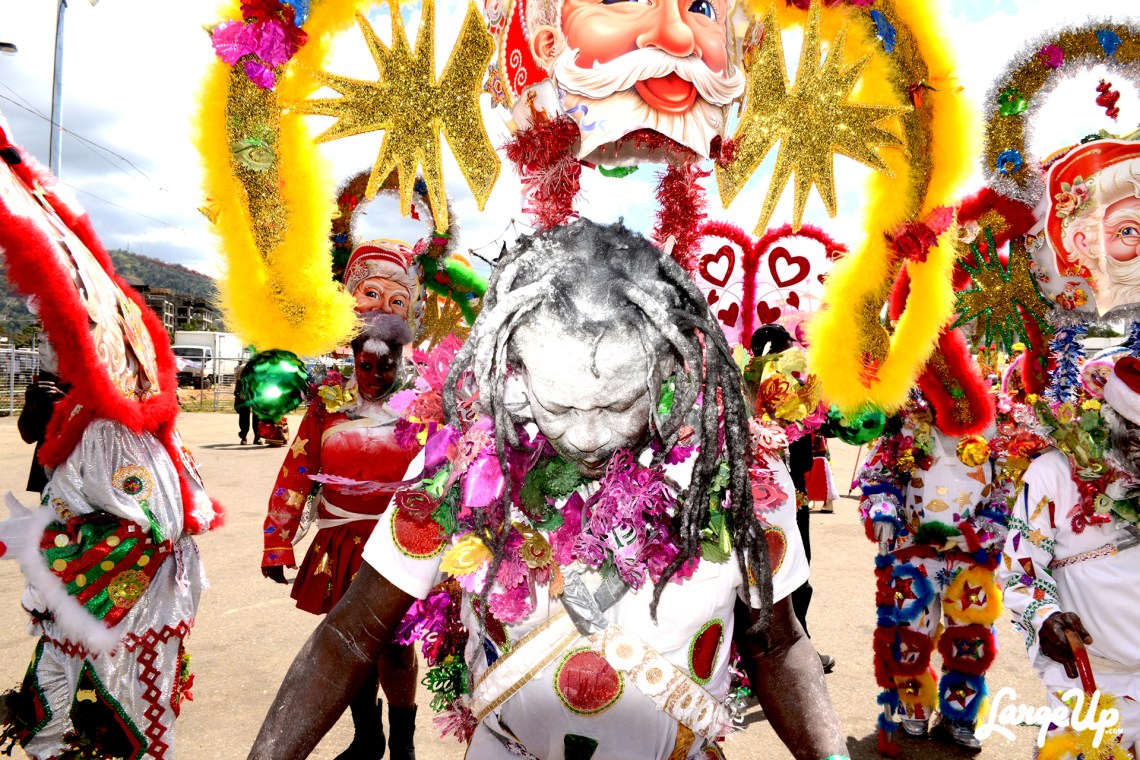

Ostensibly two days, Trinidad Carnival is more like a sprint at the end of a nearly year-long marathon. It takes a certain kind of stamina to be able to photograph a spectacle like this properly and thoroughly. Fortunately for us, we’ve got just the guy. Trini-born, Brooklyn-raised photographer Colin Williams has been returning home annually for the last decade to document the stories he sees being lost in the commercialization of Carnival. Colin’s photos depict Carnival from all angles, going beyond the fit bodies and revealing outfits that have come to symbolize the celebration, to capture the men and women in the margins. With an eye towards preserving the authentic culture of Trinidad, he takes us into the world of Fancy Indians, Midnight Robbers, Saga Boys and other staple characters whose elaborate costumes symbolize Carnival’s roots in the most personal of ways.

For Colin, Carnival starts early morning on “Fantastic Friday,” when he lands at Piarco Airport from New York, and heads straight to the pre-dawn celebration of Carnival’s past known as Canboulay. (Check out Colin’s photos from Canboulay here). After a weekend filled with fetes, family and the last preparations for Carnival, it’s time for J’Ouvert, with its explosion of powder and paint. Only then does Carnival, as most tourists and visitors experience it, begin, lasting from early morning Monday through Tuesday afternoon, with precious little room for sleep. In an effort to show the full tapestry of Carnival, we asked Colin to take us through the journey that produces the images you see here, in our largest photo feature yet.

Take us through your arrival in Trinidad. What are you setting out to accomplish?

I flew out of New York at 8 o clock and got into Trinidad at 2:30 am, and went straight to Kambule for 3 o’ clock. That’s when the [participants] start to gather around. Kambule ends around 8 or 9, when the sun comes up. Now. I worked all day [before I left]—you don’t sleep by then. You’re waking up at 7 o’clock Thursday, prepping, picking up equipment, making your final calls as far as your airline, your pickups, your contacts on the main island.

Getting into Trinidad when I arrive, you need transportation. The local car service is already shut down—you have to hire a private person, or get a family member. And they have to understand why you’re not going home to sleep when they’re picking you up at 2 in the morning. To them it’s a party, to you it’s trying to preserve a culture that soon could be extinct. Because it’s not just about the feathers and beautiful bodies, it’s about the actual Carnival itself and the reasons why we celebrate Carnival, and it all starts with Kambule. It is not given any mainstream recognition. It’s not part of the New York Times writeup, it’s not in Travel and Leisure. The only way to do this is because you really love it, and because you’re trying to capture a culture that is getting watered down, and a story that is no longer being told. And that is the entire story of Carnival.

What about the following days?

It’s hours, you can’t call it days. Saturday, you’re seeing Kiddie Carnival. They are the ones where you are seeing the real essence of carnival in the Caribbean. They still have the beautiful costumes that are well made at home, and not in China or somewhere else. That is the little window of hope. Without them knowing it, that’s what they are doing. I don’t think that’s a strategy that we’ll make these costumes and when these kids grow up they’ll know how to bend wire. But the showmanship, the Broadway play on the streets, that is what you see the kids doing. They can be in the hot sun for hours but they’re dealing with it because that’s their culture. They have it.

When do you rest?

A real solid rest? I’m sleeping maximum four hours. When you go out Saturday night, you stay out Saturday night, Sunday morning I’m shooting party people, and I take my rest from like 11 to 4. And then you go back out, you head to see the [Paramin] Blue Devils when they come out. You have to get a special vehicle to go where they are. That is Sunday, when the dragon comes out of the den.

There’s so much going on at Carnival, you can’t possibly capture everything that’s around you at one moment. How do you choose which shots to take?

What I do is, I am no longer a photographer, I become a masquerader with a fancy camera. I am always in the revelers. I don’t look for lighting or the ideal situation because there’s never an ideal situation. Everyone has their little thing, and it’s up to you with the eye and framing to capture the photo. The journalistic approach is out, because the images I photograph aren’t the ones you see on the carnival magazines that come out. If you are not in Carnival yourself, you are not going to see these images I’m taking.

I try to bring people into the movie or the play of Carnival. You know how when you look at film credits you see everyone, the prop man and the stunt doubles? I make sure everyone—the pan man, the doubles man, the kids—gets credit. I am looking for the detail of the makeup, the detail of the accessories. I want you to see the time it takes for people to put paint on their face. You should feel or taste the sweat coming down people’s face, or see the pain in their eyes because they carried this heavy costume for how many miles all day on the hot sun. You are going to get the feeling they have before they notice me and get in their grand pose, whether that is tiredness or excitement. I am not a spectator in the Pavilion looking down. When I see gladiators, I become a gladiator, when I see a beautiful girl I become that girl’s boyfriend. You’re gonna see what he looks at.

What are you looking for in a person that’s going to make you stop to get their shot?

I shoot characters. There was this guy coming off the stage, and he was probably about 110 pounds, and he had painted on abs and a chest. He had these little Speedos on and he looked like a cricket. Everybody was laughing, but it was just the freedom of him coming out and expressing himself in that way. I will capture a kid’s expression while he is looking at those folks, holding a snowcone. I look for the person who is giving me one of the dynamics of Carnival that I didn’t yet catch.

What I try to do most of all is this: People forget why they come to Trinidad & Tobago for Carnival. We don’t samba. That is for Brazil. What we do is we revel, we wine and we get on, but folks come in and they want to give me the Sports Illustrated pose. So I provoke people to remind them why they’re there. I orchestrate things. I will say something like, “Why are you coming at me?” and they will be taken aback, and break out of their shell. This is not gonna happen for the next 365 days, if you even get back there. This is why you went to gym every day, this is why you don’t eat carbs. You do everything to prepare for this moment, and when you get there, you forget.

I don’t do retakes and I don’t show people their photos. This is carnival, everything is as is. It’s perfect already. People will say, “I wasn’t ready.” You’re always ready. I want those people who didn’t make it, or who haven’t experienced it, to feel the vibrancy of Carnival by looking through my images. You will have much more appreciation for the people who get into the costumes on Monday and Tuesday, and the meaning of the Tamboo Bamboo and the jab jab, and get an idea of the multiculturalness of Trinidad & Tobago, the oneness we are supposed to have. Everyone in Trinidad celebrates Carnival because it is celebrating something that was going to be denied. The right to [celebrate] was granted to you, and then it was gonna be taken from you. It was granted by the French and when the English came, they said no. The [original masqueraders] stood for something that is now being portrayed throughout North America, but that is not being told.

There is a reason for everything you see at Carnival—the mud, the paint. It’s fun, but there is a different layer behind it. It’s like in religion, there are certain laws and rituals you are given to do, but people don’t know why or what it means. You have all these different carnivals in the Caribbean, we are all going to wind up being the same carnival and forget about these characters that are unique to this Carnival. Trinidad has a crazy culture and it’s not just one, there are so many cultures that came into this one.

I’ve seen some characters turn up again in your photos in different years. Do you have people you try to find and shoot every year?

I try to document as much of these old characters because they are the backbone of carnival. To make sure they are still there. After I photographed one of these guys, a woman contacted me and said this is her uncle’s friend and he’s in the hospital, and that was his last year of playing carnival. These people are so grateful when I photograph them. They are overlooked. When I look around, I don’t see any other photographers, they all go to the end and get the same thing. Trinidad & Tobago Carnival, what I like about it is: it’s like a river. Or the sea. You can’t control it. People want to control it and have everybody congregate in the stadium at a certain time. Leave Carnival in the streets. It’s a street festivity. Don’t put it in a bottle and make it something it’s not meant to be. Give it to the streets, whatever direction they want to go in. They give you a route, and they will say [a certain place] is not part of a route, but there will be a truck that decided to go where it wanted. It’s like if you were at the St Patrick’s Day Parade, and they just turned at World Trade Center. That happens in Trinidad. The tangibleness of Trinidad & Tobago made Carnival what it is. You get on a plane, hop off, meet a taxi driver and step out at a local bar and get into the adventure.

The man in the really elaborate orange and red Wild Indian costume has turned up a few times in your work. How long have you been shooting him?

I have been seeing him before but I was always under the lens of the pretty girls. And when I looked at my photos from 2005 to 2010, they were all the same. I thought that was something missing from the feathers and bodies, and that’s when I decided to dig in. I realized there is this whole entire culture encyclopedia, or Google of Carnival, that people are not searching.